Utilizing large, graph-based, pre-trained machine learned potentials in atomistic simulations#

Abstract#

The most recent, state of the art machine learned potentials in atomistic simulations are based on graph models that are trained on large (1M+) datasets. These models can be downloaded and used in a wide array of applications ranging from catalysis to materials properties. These pre-trained models can be used on their own, to accelerate DFT calculation, and they can also be used as a starting point to fine-tune new models for specific tasks. In this workshop we will focus on large, graph-based, pre-trained machine learned models from the Open Catalyst Project (OCP) to showcase how they can be used for these purposes. OCP provides several pre-trained models for a variety of tasks related to atomistic simulations. We will explain what these models are, how they differ, and details of the datasets they are trained from. We will introduce an Atomic Simulation Environment (ase) calculator that leverages an OCP pre-trained model for typical simulation tasks including adsorbate geometry relaxation, adsorption energy calculations, and reaction energies. We will show how pre-trained models can be fine-tuned on new data sets for new tasks. We will also discuss current limitations of the models and opportunities for future research. Participants will need a laptop with internet capability. A computational environment accessible via the internet will be provided.

Introduction#

Density functional theory (DFT) has been a mainstay in molecular simulation, but its high computational cost limits the number and size of simulations that are practical. Over the past two decades machine learning has increasingly been used to build surrogate models to supplement DFT. We call these models machine learned potentials (MLP) In the early days, neural networks were trained using the cartesian coordinates of atomistic systems as features with some success. These features lack important physical properties, notably they lack invariance to rotations, translations and permutations, and they are extensive features, which limit them to the specific system being investigated. About 15 years ago, a new set of features called symmetry functions were developed that were intensive, and which had these invariances. These functions enabled substantial progress in MLP, but they had a few important limitations. First, the size of the feature vector scaled quadratically with the number of elements, practically limiting the MLP to 4-5 elements. Second, composition was usually implicit in the functions, which limited the transferrability of the MLP to new systems. Finally, these functions were “hand-crafted”, with limited or no adaptability to the systems being explored, thus one needed to use judgement and experience to select them. While progess has been made in mitigating these limitations, a new approach has overtaken these methods.

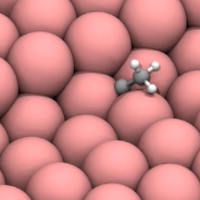

Today, the state of the art in machine learned potentials uses graph convolutions to generate the feature vectors. In this approach, atomistic systems are represented as graphs where each node is an atom, and the edges connect the nodes (atoms) and roughly represent interactions or bonds between atoms. Then, there are machine learnable convolution functions that operate on the graph to generate feature vectors. These operators can work on pairs, triplets and quadruplets of nodes to compute “messages” that are passed to the central node (atom) and accumulated into the feature vector. This feature generate method can be constructed with all the desired invariances, the functions are machine learnable, and adapt to the systems being studied, and it scales well to high numbers of elements (the current models handle 50+ elements). These kind of MLPs began appearing regularly in the literature around 2016.

Today an MLP consists of three things:

A model that takes an atomistic system, generates features and relates those features to some output.

A dataset that provides the atomistic systems and the desired output labels. This label could be energy, forces, or other atomistic properties.

A checkpoint that stores the trained model for use in predictions.

The Open Catalyst Project (OCP) is an umbrella for these machine learned potential models, data sets, and checkpoints from training.

Models#

OCP provides several models. Each model represents a different approach to featurization, and a different machine learning architecture. The models can be used for different tasks, and you will find different checkpoints associated with different datasets and tasks.

Datasets / Tasks#

OCP provides several different datasets that correspond to different tasks that range from predicting energy and forces from structures to Bader charges, relaxation energies, and others.

Checkpoints#

To use a pre-trained model you need to have ocp installed. Then you need to choose a checkpoint and config file which will be loaded to configure OCP for the predictions you want to make. There are two approaches to running OCP, via scripts in a shell, or using an ASE compatible calculator.

We will focus on the ASE compatible calculator here. To facilitate using the checkpoints, there is a set of utilities for this tutorial. You can list the checkpoints that are readily available here:

%run ocp-tutorial.ipynb

list_checkpoints()

See https://github.com/Open-Catalyst-Project/ocp/blob/main/MODELS.md for more details.

CGCNN 200k

CGCNN 2M

CGCNN 20M

CGCNN All

DimeNet 200k

DimeNet 2M

SchNet 200k

SchNet 2M

SchNet 20M

SchNet All

DimeNet++ 200k

DimeNet++ 2M

DimeNet++ 20M

DimeNet++ All

SpinConv 2M

SpinConv All

GemNet-dT 2M

GemNet-dT All

PaiNN All

GemNet-OC 2M

GemNet-OC All

GemNet-OC All+MD

GemNet-OC-Large All+MD

SCN 2M

SCN-t4-b2 2M

SCN All+MD

eSCN-L4-M2-Lay12 2M

eSCN-L6-M2-Lay12 2M

eSCN-L6-M2-Lay12 All+MD

eSCN-L6-M3-Lay20 All+MD

EquiformerV2 (83M) 2M

EquiformerV2 (31M) All+MD

EquiformerV2 (153M) All+MD

GemNet-dT OC22

GemNet-OC OC22

GemNet-OC OC20+OC22

GemNet-OC trained with `enforce_max_neighbors_strictly=False` #467 OC20+OC22

GemNet-OC OC20->OC22

Copy one of these keys to get_checkpoint(key) to download it.

You can get a checkpoint file with one of the keys listed above like this. The resulting string is the name of the file downloaded, and you use that when creating an OCP calculator later.

checkpoint = get_checkpoint('GemNet-OC OC20+OC22')

checkpoint

'gnoc_oc22_oc20_all_s2ef.pt'

Goals for this tutorial#

This tutorial will start by using OCP in a Jupyter notebook to setup some simple calculations that use OCP to compute energy and forces, for structure optimization, and then an example of fine-tuning a model with new data.

About the compute environment#

ocp-tutorial.ipynb provides describe_ocp to output information that might be helpful in debugging.

describe_ocp()

/opt/conda/bin/python 3.9.15 | packaged by conda-forge | (main, Nov 22 2022, 15:55:03)

[GCC 10.4.0]

ocp is installed at /home/jovyan/shared-scratch/jkitchin/tutorial/ocp-tutorial/fine-tuning/ocp

ocp repo is at git commit: 52ec4b0

numba: 0.57.1

numpy: 1.24.4

ase: 3.22.1

e3nn: 0.4.4

pymatgen: 2023.5.10

torch: 1.13.1

torch.version.cuda: 11.6

torch.cuda: is_available: True

__CUDNN VERSION: 8302

__Number CUDA Devices: 1

__CUDA Device Name: NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 Ti

__CUDA Device Total Memory [GB]: 11.552096256

torch geometric: 2.2.0

Platform: Linux-5.15.0-52-generic-x86_64-with-glibc2.31

Processor: x86_64

Virtual memory: svmem(total=270098583552, available=249809203200, percent=7.5, used=19802476544, free=120864677888, active=27461500928, inactive=111639048192, buffers=3308314624, cached=126123114496, shared=67592192, slab=8342106112)

Swap memory: sswap(total=0, used=0, free=0, percent=0.0, sin=0, sout=0)

Disk usage: sdiskusage(total=1967317618688, used=299703037952, free=1567604969472, percent=16.1)

Let’s get started! Click here to open the next notebook.